RECENT AWARDS.................

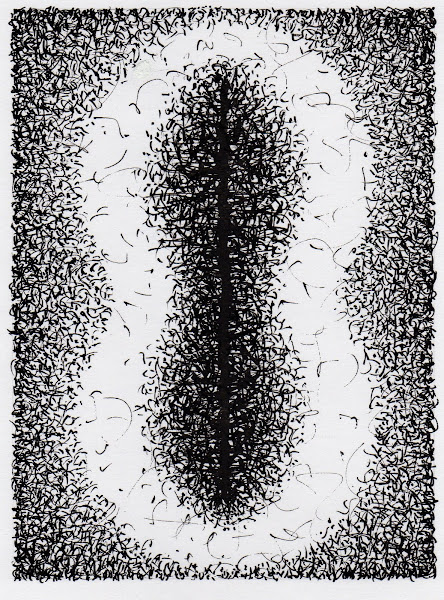

TOUCHSTONE AWARD for

silence of snow

we listen to the house

grow smaller

This haiku also gained best of issue in FROGPOND 2013 and Museum of Literature Award.

**

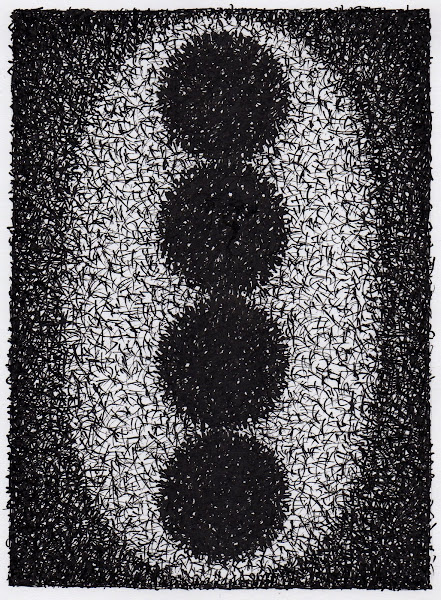

SECOND PRIZE, 'AN (COTTAGE) PRIZE' in the annual GENJUAN HAIBUN COMPETITION

for 'UNCLE WALTER'

Uncle Walter

Just after the war, I am sent

to Aunt Cath’s in Burnham Thorpe, Nelson’s birthplace. It nestles between the

Holkham estate and the great empty expanse of salt marsh that lines the coast;

a world of mystery and magic. Steam engines rumble across fields, ‘night soil’

men visit in the dark. The only light is oil, ghost stories of black dogs and

headless horsemen abound.

“Uncle Walter’s a dirty old

chap” says my aunt Cath, “he washes his face in that old water butt where we drowned

the kittens”.

by the flint cottage

into green depths

spiral

nymphs

from his pocket

a coiled ferret

unsprung

Uncle has a black pony called

Bess that pulls a trap. I help him collect hay from the verges, using a sickle.

On our return I perch on top, soak up its smell; listen to the rhythm of

hooves, to him talking with Bess in that sing song voice. He has a special way

with her; she seems to read his mind. I ask him if it’s true.

down Old Lowses

at a pace through

wreaths

of roll-up smoke

He tells me of Suffolk

“A toad’s bone?” I repeat.

“Yes boy, a sort of wishbone.

You catch a toad and hangs it in a thorn till its all dried up, then you buries

it in the ant’s fortress. On the full moon you throws it in the beck. If the

hip bone swims upstream, you catch it and keeps it under your arm. Its this

bone my boy, that gives you the power.

We arrive home and unload the

hay, Bess, out of her harness, stands in the yard; he smiles and murmurs something

to her. She nods and walks quietly into the stable.

whispers from childhood

still close

in the darkness